Reverse Engineering Night Raid

Night Raid

Introduction

When I was a kid, probably somewhere around 7 or 8 years old, a friend of mine introduced me to a video game called Night Raid. Created in 1992 and developed by ARGO Games, and published by Software Creations, it’s not likely that you’ve ever heard of it. It was just some niche game written by Jason Blochowiak, with art from Don Glassford and music by Robert Prince, that very few people ever played, but had a big impact on me.

After starting to write this I discovered that Night Raid is a remake of a very popular 1982 game called Paratrooper. I hadn’t heard of Paratrooper and I wasn’t even born when it came out. I think Night Raid improved on the classic and even added a few things. You can see a bit of Paratrooper here.

As I remember it, the friend who gave me the game also told me that there were 300 waves (called “waves in the game). I don’t know why that statement stuck with me, but it may have been because I was only able to complete a handful of waves before losing. Even the thought of twenty waves seemed daunting.

Years later, I would think about Night Raid and its three hundred waves from time to time. I couldn’t imagine it had 300 waves, but maybe it just kept going and getting harder and harder until you eventually lost, similar to a Rogue-Like.

This theory of infinite waves didn’t seem to make much sense, for one simple reason. Every so many waves in Night Raid you’re treated to an intermission animation between waves called “intermission”. In one intermission, a helicopter brings an outhouse for your character to use. In another, your character has pizza delivered. How would they be able to do that infinitely? How many intermissions existed, and more importantly, what were they?

More time had gone by, and I was sitting around bored one day and decided to see what I could find about this old game that kept popping into my head. I quickly found it at My Abandonware. I fired up DOSBox and started playing it. The soundtrack provided a wave of nostalgia I didn’t expect, the title song still slaps.

As a reverse engineer, I immediately thought to myself: “You know, I could probably figure out how many waves there are pretty easily”.

NOTE: These are words I pretty much can’t stop myself from saying. The phrase “Pretty easily” just really should be removed from my vocabulary.

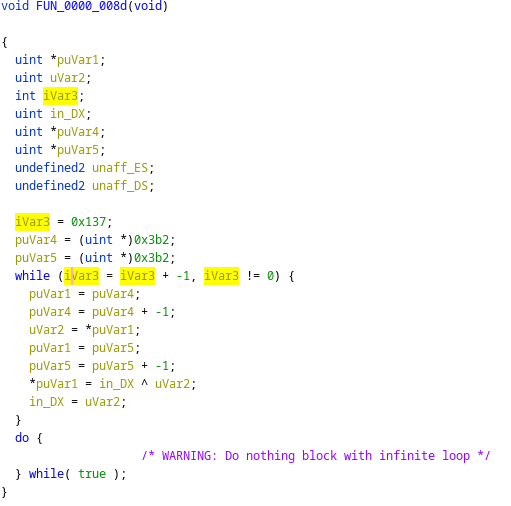

I threw the binary into Ghidra and much to my dismay, I was met with the following:

PKLite Packer

It looks like my time estimation just went out of the window. What did I expect? an MS-DOS executable to have symbols compiled in and no obfuscation?

Though this looks like there’s only one function call, what you’re really looking at is what’s called a “packer”. Packers are usually used for one or more of the following reasons:

- Obfuscate code and protect intellectual property from pirating by making reverse engineering harder

- Compress the size of the application

- Defeat antivirus software

In recent years, packers are more often used to protect intellectual property and defeat anti-virus software. However, in the 1990’s making a binary smaller was a bigger goal as diskette capacities were very limited (1.44 megabytes). Did anyone else install Windows 95 on a PC from floppy disks?

Because I was thinking about this, I decided to look up how many diskettes it took to install Windows 95. The answer is 13. That’s an insane number and when you consider the cost of those disks and the cost of distribution, you can see why companies were keen to keep binaries on disk as small as possible. In addition, there was an OSR 2.1 version that took 26 diskettes.

It’s tempting at this point to start working through the disassembly and running the program dynamically to unpack the executable by hand. But my time is limited these days and I decided a better course of action was to see if someone knew something about this packer before I began. Why re-invent the wheel?

In looking for strings in the binary, there were nearly none. Just an error Not enough memory$- and the message 1PKLITE Corp. 1990-92 PKWARE Inc. All rights Reserved.

Gee Wiz Info: MS-DOS had two types of strings, ASCIZ and ASCII strings. ASCIZ strings end in a null byte (\0) and ASCII strings ended in a ‘$’. Kinda weird huh?

I spent some amount of time looking for anything that related to a PKLITE packer. Anyone from the era would have been familiar with the PKWare company, as the maker of PKZIP. However, all I could find was a brief description of it.

I quickly got distracted and realized I should probably get back to work.

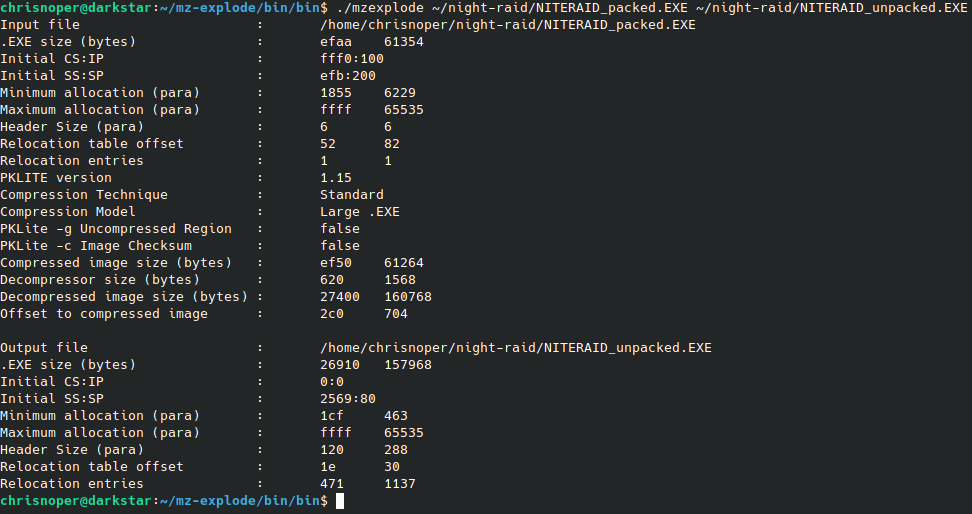

Several years later, I was discussing games we liked to play as a kid when Night Raid came up. I decided to take another look. Maybe my google-fu has gotten better, or maybe new information had come to light, but when searching for an unpacker I was able to find a Wikipedia article on PKLite. This was far more information than I’d been able to find previously. It also leads me to the MZ-Explode project. This project can unpack a PKLite binary and return it to its original form. Downloading and compiling the project gave me the following output:

The program worked great. According to the documentation the tool was created from the disassembly of the original PKLite tool, so it handles all the various edge cases that can arise.

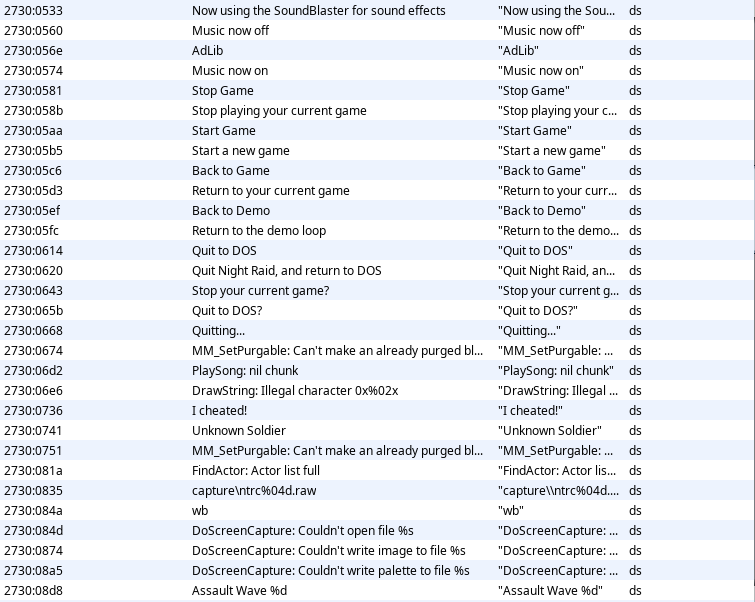

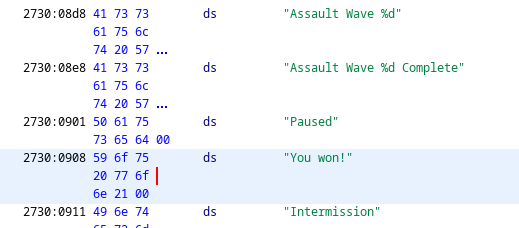

With this problem out of the way I thought to myself “Nice, now this will be easy…”. I loaded the new binary up in Ghidra and looked for strings. Here is some of the output:

There’s a lot of great stuff here. In fact, strings titled Intermission, You won!, and Assault Wave %d all seem like great starting places. I quickly decided that if I could find the variable that Assault Wave %d is using to create its format string, then I could find other places that variable is used and identify what the maximum value could be.

However, when I looked at these strings I saw the following:

None of these strings have any cross-references. None. Oof.

In reverse engineering work, finding a place to start is the most important first step. You can’t look at every single instruction or line of code, especially in larger binaries. In small toy programs like capture the flag challenges, it’s feasible to look through the majority of a binary. But for something as large as a 90’s MS-DOS style video game, it can be an endless sea of instructions, data, and code.

But why weren’t there any cross-references?

MS-DOS 16-bit Segmentation

One of the biggest problems is the 16-bit memory segmentation model of MS-DOS real mode.

NOTE: There are several modes, real and protected. The following discussion only covers real-mode memory segmentation.

If you’re a modern-day programmer of low-level languages such as C and (to a lesser extent modern C++), you’ve likely dealt with pointers, and by extension memory addresses. In modern 32-bit computers running modern operating systems, a pointer to a memory location is just the 4-byte address of the value in virtual memory. In a 64-bit machine, these pointers are 8-bytes long. But the address space is linear, and these address sizes are great because the addresses fit perfectly into one register.

However, it’s more complicated on Intel systems running MS-DOS. The processor can be put into several modes and one of the most common modes for video games was “real mode”. I’ll spare you the details, but the 8086 processor was able to address 20 address lines (or 1MB of space), but only had registers that were 16-bits in size (64KB of space).

This is a problem whenever you have an instruction that dereferences a register for a memory read, for example:

mov bx, [ax] ; Moves what AX points to into BX

This is a problem because AX can never be a value that reaches the majority of the available address space the processor is capable of handling. The solution to this is to have a set of special registers called segment registers. These registers would be for the top portion of the addressing scheme, allowing the software to utilize all 20 address lines. This segment register would be the 16 most significant bits in the total 20-bit address.

| Segment Register | Description |

|---|---|

| CS | Code Segment |

| DS | Data Segment |

| ES | Extra Segment |

| SS | Stack Segment |

To calculate the full 20-bit address of the memory location you were trying to access, the segment register value was shifted left by 4 bits, and then the offset register was added. Example (from Wikipedia).

DS = 0x06EF

AX = 0x8124

0000 0110 1110 1111 0000 = DS << 4

+ 0001 0010 0011 0100 = AX

---------------------------------------

0000 1000 0001 0010 0100 = Final Address

You’d be correct if you noticed that multiple-segmented addresses can all resolve to the same linear address. In the above example, the final address 0x08124 could be 06EF:1234, 0812:0004, or 0000:8124.

A natural question to ask is: “How do I determine the value of DS at any given point in the disassembly?” The answer is that it’s whatever it was set to at any point during execution. It’s up to the compiler to make sure that it gets set correctly before the memory access happens, but that can be set at any time. This means Ghidra needs to track this value through the program flow, and across CALL instructions.

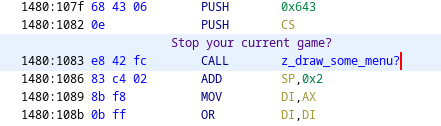

Ghidra does a good job of tracking the segment registers. At almost any point you can check the value of DS or CS and it can tell you, based on context, the value of that register. However, in other cases, it’s simply not able to figure it out. Here’s an example:

In this case, the value of 0x643 will get pushed on the stack as a parameter to the poorly named function z_draw_some_menu. This 0x643 refers to the offset in a data segment that contains the string Stop your current game?. This address will be resolved with the correct DS (if it’s not already set) inside of the function z_draw_some_menu but by that point, we won’t directly deal with the value 0x643 but will be dealing with “some variable on the stack” (which in this case happens to be 0x643). Therefore, Ghidra doesn’t know that 0x643 is actually a pointer to a data segment string. Ghidra just thinks it’s a value from the stack, an integer of some kind.

Deviations

This article is going to present this information as if it happened linearly. It didn’t, like most reverse engineering. Many paths were taken, and many were abandoned.

From the point of having no string references, I went down a bunch of different paths to help find the main game loop. Some of these were just for fun, others were more targeted toward my end goal. In doing so I figured out a ton of information about how the game worked. The following is a short list of things I discovered

- How keyboard input worked

- How mouse input worked

- How the main menu was being handled

- How the sound worked

- How graphics are rendered in Mode 13h

- File I/O

- A bit about how the

GRAPHICS.NTRfile is organized

All of those things likely warrant their own article. I won’t go into those right now.

Solution

There were two major breakthroughs that finally solved the problem. The first breakthrough came when I was investigating the format of the GRAPHICS.NTR file. It dawned on me that to process the graphics file, the game would have to open it at some point in the boot process. This led me to try to find cross-references to the GRAPHICS.NTR string. Obviously, as expected there were none.

But the file had to be opened at some point. How do you open a file in MS-DOS? Through an interrupt.

MS-DOS Interrupts

MS-DOS works as an interrupt-based system. MS-DOS came packed full of tons of useful functionality the programmer was expected to interact with directly as opposed to how applications now interact more commonly through standard library functions. Linux works similarly with its use of syscalls.

As an example, if you wanted to print a string to the console, you’d likely write something like the following in assembly:

main:

lea dx, hello ; DX contains the string to be printed.

mov ah, 9h ; AH is "Write String to STDOUT"

int 21h ; DOS Functions

hello db 10,13,"Hello World$"

There are tons of interrupts, and the resource Ralf Browns Interrupt List Is the gold standard listing.

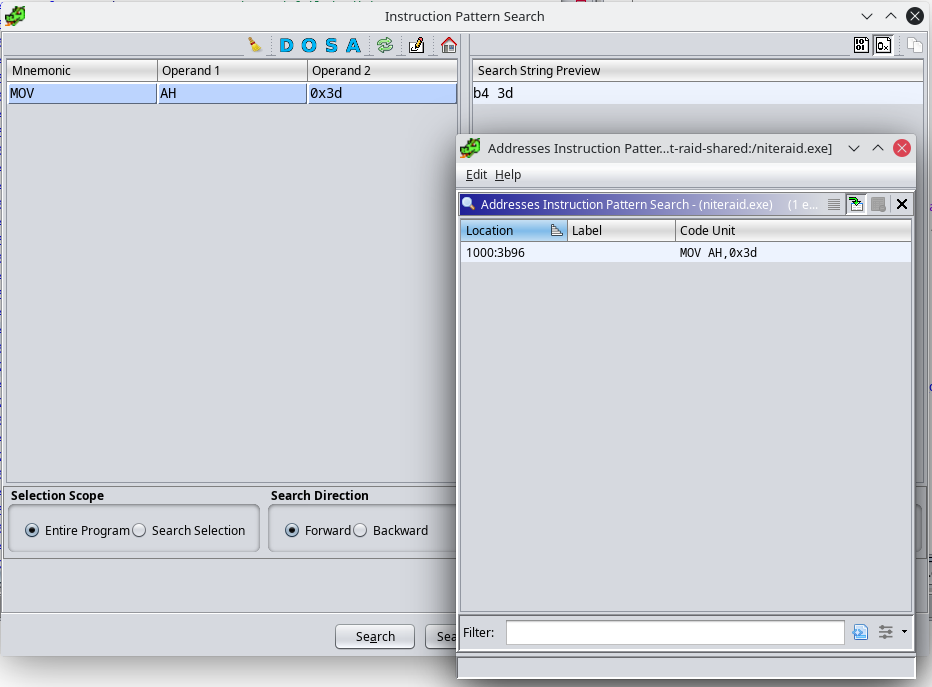

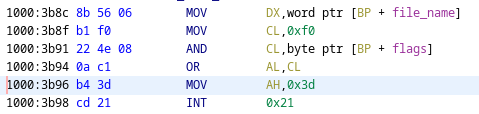

In hunting through Ralf Brown’s list, we find the following entry: Int 21/AH=3Dh - DOS 2+ - Open - Open existing file.

This means when we find int 21 with AH = 0x3D then we have found a file being opened.

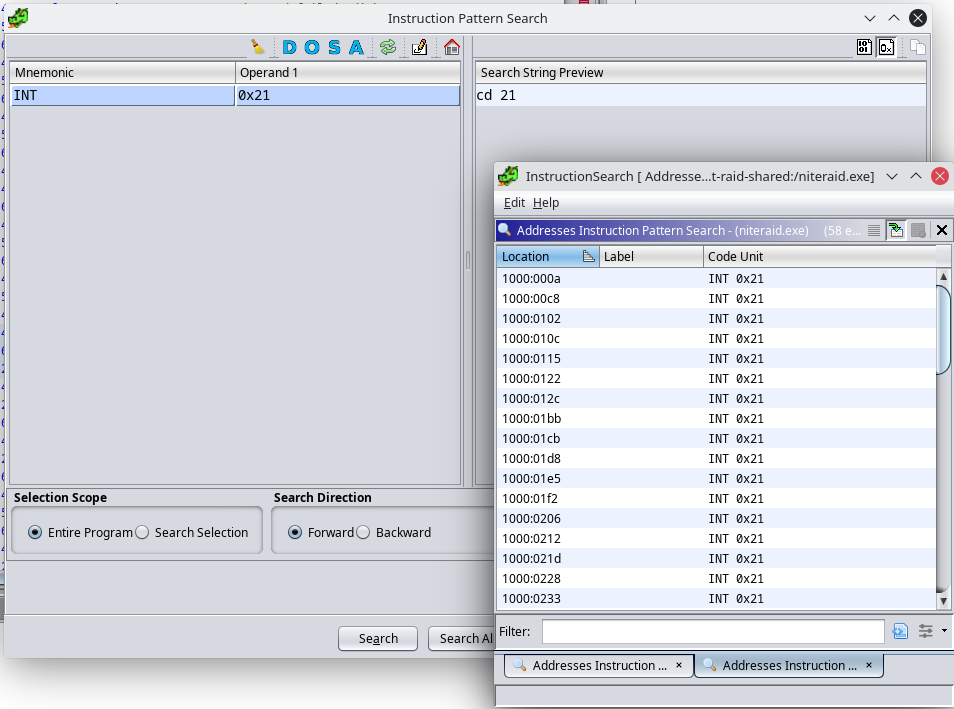

Ghidra has a great instruction pattern search tool under: Search -> For Instruction Patterns

I happen to know that CD 21 is the instruction for int 21h, but if you didn’t know that you could use pwntools assembler, or some other Keystone wrapper. Below are all the cross-references for int 21h. It can be a fun exercise to go through each of these and figure out what they all do.

However, this search for int 21 has a big problem: It’s used everywhere. int 21 is probably the most used interrupt for any application. Now, I could manually go through all of these references, or I could take a gamble and assume that there aren’t that many places with an instruction such as mov ah, 3dh (opcode b4 3d). Let’s plug that into the instruction matcher:

Bingo! Only one reference. If we visit that location, we see that it is indeed being used with an int 21h. Perfect.

This means we have found our open file routine at 1000:3acb.

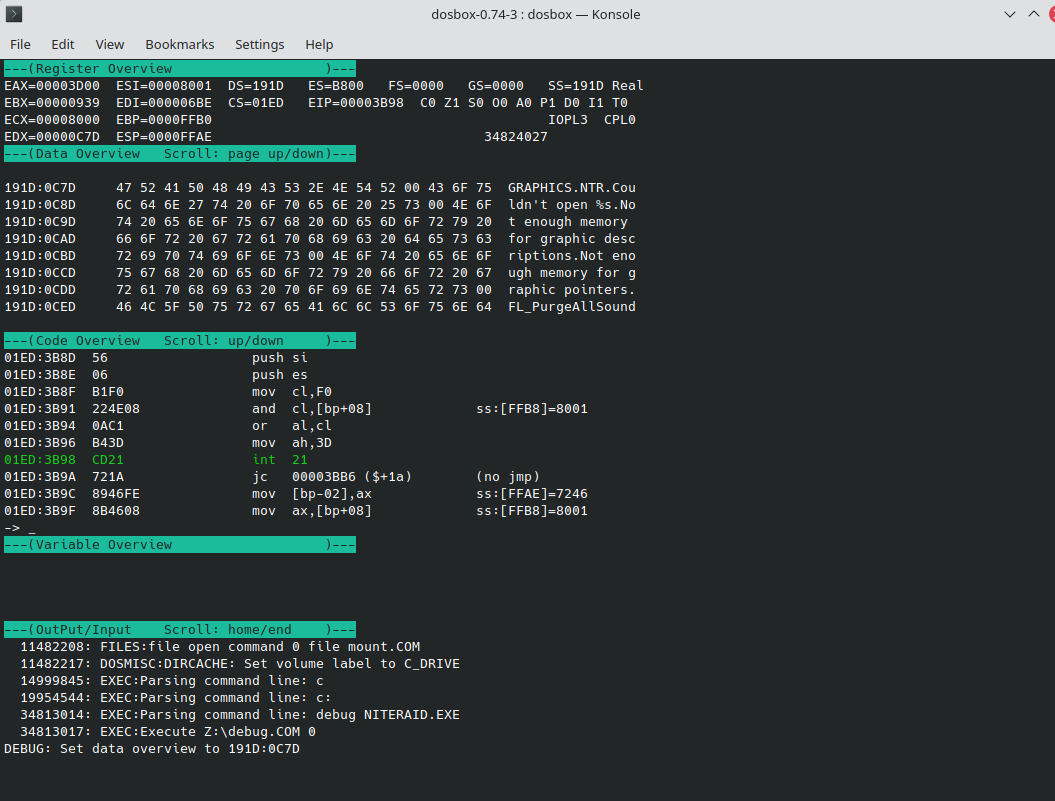

My annotations already give away the answer but the next thing to do was to identify what variables were on the stack such as the filename and the flags. This was easy using Ralf Browns interrupt reference which says the following:

| Register | Use |

|---|---|

| AH | Function |

| AL | Access Mode (Flags) |

| DS:DX | ASCIZ Filename |

| CL | Attribute mask |

This means that the combined address of DS:DX contains our filename.

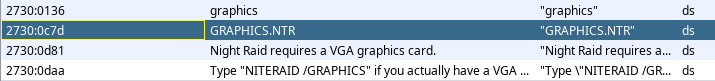

If we walk back a couple functions from our current location from: 1000:3acb -> 1000:3a19 -> 1d6c:047b We will see that there is a function call with the value 0xc7d pushed onto the stack. Hmm, I wonder what that file name might be.

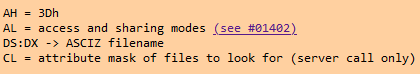

DOSBox

So far we’ve only talked about static analysis of the binary. But we can incorporate dynamic analysis as well with DOSBox. If you’re unfamiliar DOSBox is an emulator used to emulate an MS-DOS machine from the 90s. Honestly, this project has been around for a long time and I just realized that it runs on Windows Mac OS and Linux. I’ve tested all three and they all seem to work flawlessly which is impressive.

DOSBox also comes with a debugger, if you enable it when you compile from source. To do so follow the instructions on Vogons.

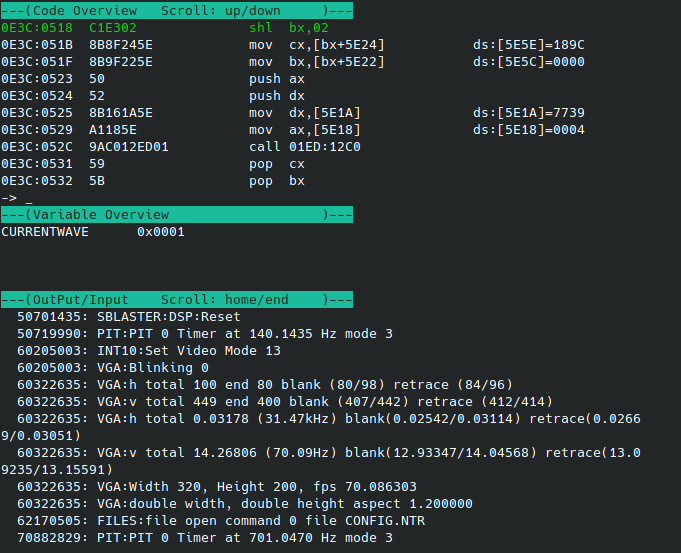

It looks something like this:

It’s a full-featured debugger and has specialized commands to handle interrupts. Let’s use this to our advantage.

Cross Referencing Strings

First, we’ll want to mount and launch Night Raid with the following commands:

Z:\> mount c ~/night-raid

Z:\> c:

C:\>DEBUG NITERAID.EXE

Why is the game called Night Raid, but the executable is NITERAID.EXE? Honestly, I don’t know. But if I had to guess it’s because DOS file names can be 8 characters + a 3 letter extension after a period. NIGHTRAID would be 9 characters, but NITERAID fits into 8 characters. Using

NIGHTRAID.EXEwould cause it to show up asNIGHTR~1.exeon adirlisting and this wouldn’t have been a very good user experience. Many versions of MS-DOS supported longer file names to be shown, but DOSBox doesn’t seem to have that feature.

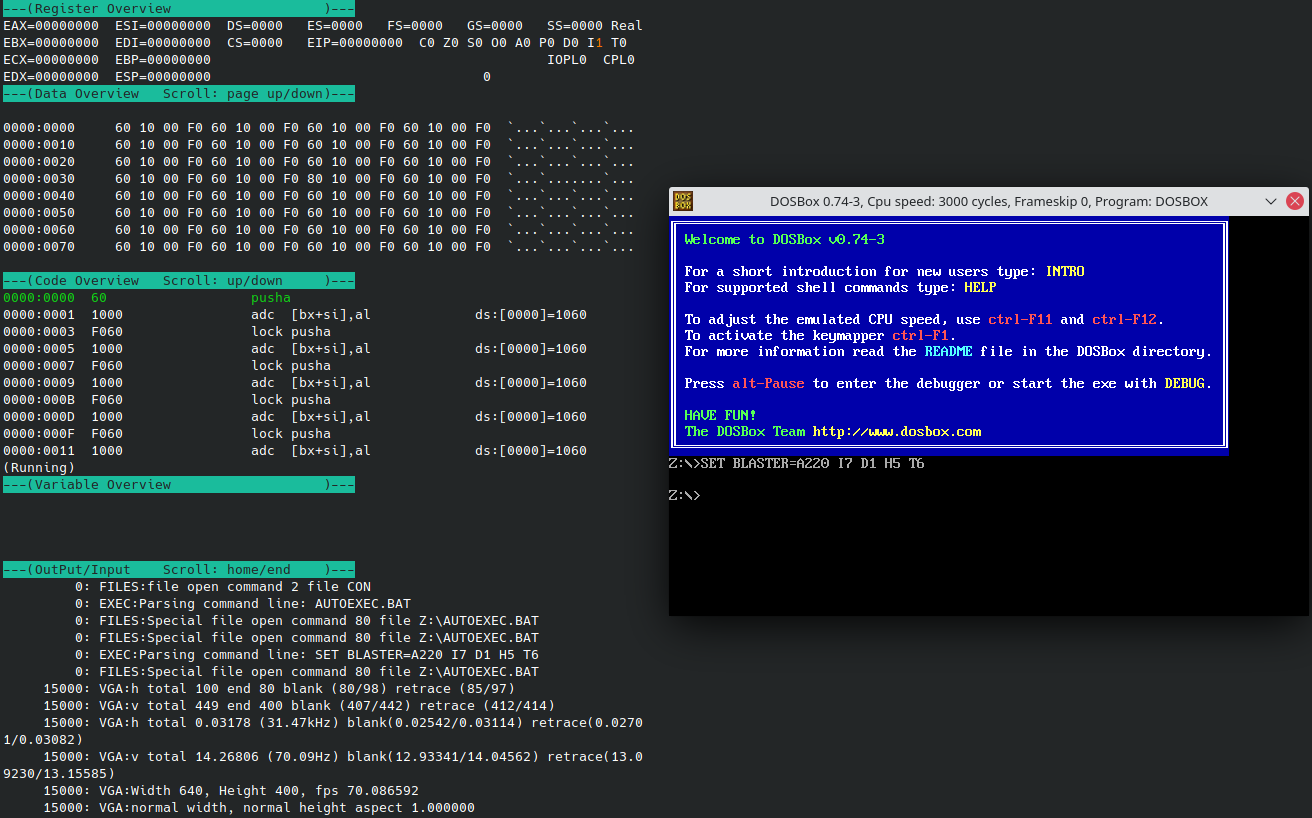

I decided to set a breakpoint on our file open interrupt and see if we can catch GRAPHICS.NTR being opened. I figured that might give me a fighting chance to create some sort of translation between 2-byte offsets into an unknown data segment and the actual location of the string.

bpint 21 3d

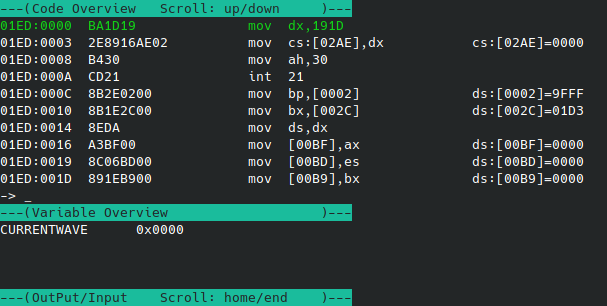

Pressing F5 (to continue execution). We see the following in the debugger when we break:

In this image, I have set the data viewer to the address of DS:DX. You can see that DS:DX is a pointer to GRAPHICS.NTR. As it turns out the graphics file is the first thing that gets opened. This also tells us that the data segment that contains our string data is 0x191D and the offset is 0x0C7D. Let’s have another look at the same string in Ghidra.

The same string in Ghidra has a segment register of 0x2730 and an offset of 0x0c7d. In fact, if we look at all of the string data in Ghidra, we will see that they all fall into the same data segment. This means that we can ignore what the data segment is, and focus only on the offset, to find cross-references for our strings.

As our main goal is to find the number of waves in the game, let’s look for a string that might reference the wave we’re currently on.

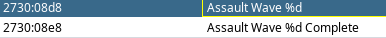

There are two:

Let’s see if we can find any references to the value 0x08d8. We already know that this value will be pushed onto the stack as a parameter to a function. Ghidra provides scaler search functionality via Search -> For Scalars.

This reveals only one location (perfect!):

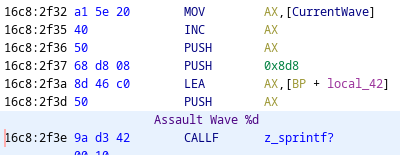

The screenshot gives it away, but we can see this value is being pushed as the 2nd parameter in the function call to some sort of sprintf equivalent function. We know this is some sort of sprintf because our string Assault Wave %d is a format string, and a value is being passed to fill that format string location, and the first parameter is a stack variable which is likely our output string.

The value pushed third onto the stack is the value that is replacing the %d in our format string. In this case, it’s likely the current wave that we are on. One is added to this value because the value stored starts at 0, and increments from there, but when the message is displayed to the user, saying Assault Wave 0 doesn’t make much sense. The player will probably want to see Assault Wave 1.

So now we think we know the variable that deals with what wave, or wave we’re on. Let’s test it out.

If we restart, Night Raid we can use the IV name to create a variable name that we can then monitor for changes. In our case, the full command will be IV 191D:205e currentWave. This will place the value of 191d:205e with a friendly name, into our variable overview, as seen below:

Play the game through the first wave and we can see the change when the next wave starts:

As you can see the wave has incremented and is one less than the wave number drawn to the screen, just as expected.

As you can see the wave has incremented and is one less than the wave number drawn to the screen, just as expected.

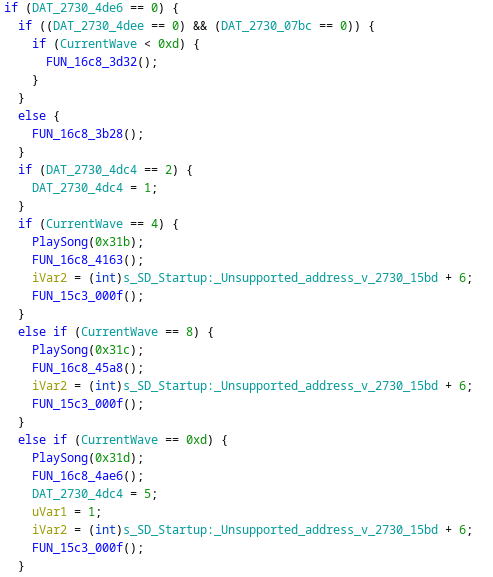

So now we know the current wave number, let’s go and check out its cross-references. In Ghidra the offset to the currentWave in our code is 2730:205e. Looking at the list of cross-references, there are quite a few, where one stands out: 16c8:4e52. This function appears to check the current wave many times, for specific values.

As mentioned above, every so many waves, a unique intermission animation plays. If we play through the game and watch the value of currentWave we’ll see that those unique animations line up with the values being checked against. It also looks like the biggest, and the last animation might be 0xd.

Another thing to notice is that the animation numbers listed here are one more than when the animation actually plays. This means the first animation will play after wave 3, after wave 7, and finally after wave 13.

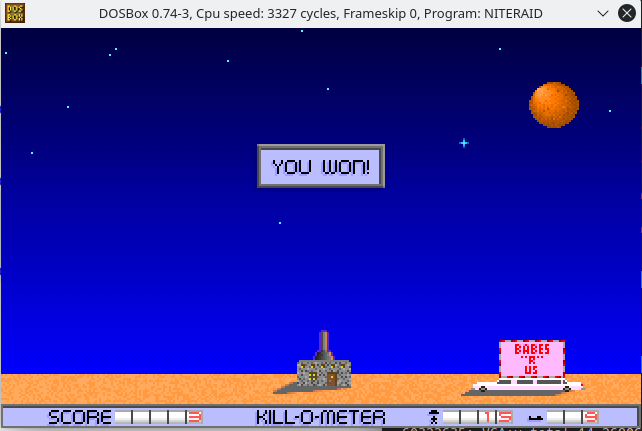

Now, back to Night Raid, let’s test this. Load up the first wave, then while it’s playing set the current wave to 0xc and play through the end of the current wave.

Receive your “You Won” animation.

Conclusion

There are not 300 waves, and there are not infinite waves. There are just 13.

FAQ

Q: Why did you just look for “You Won”. A: I did, but there are no direct cross-references to that string.

Q: Did you find anything else in looking? A: A ton of really interesting stuff, more related to the nuts and bolts of writing a video game in MS-DOS. In addition, lots of other variables were identified such as the score, paratroopers killed and airplanes destroyed.

Q: What would you look at in the future? A: I didn’t really get time to see if there were any unknown key commands or cheat codes beyond what are in the README.

Q: Did you not know you can warp waves? A: Yes I did know I could warp waves. AFAIK you can’t get to the last several waves.

Resources

- Best interrupt reference in existence: Ralf Brown Interrupt List

- Keyboard input scancodes and values: Scan Codes

- Serial Ports: Serial Port Reference

- VGA/SVGA Memory Programming: VGA/SVGA

- Dos programming Manual: DOS Programming

- Mode 13H palette changing and reading: Mode 13h